Sending a prospective seller a letter of intent is a bit like asking a girl out to the homecoming dance. If she says yes, you start to prepare for the big night. However, there is no guarantee she won’t ditch you for the varsity quarterback the night before. LOIs formalize the invite to start a deal process but are no guarantee the deal will go through.

Only put clauses into the LOI that are reasonably enforceable (from a time, cost and legal standpoint) and those which are going to increase your chances of finalizing the deal. In the previous discussion, I mentioned that speed to close was my biggest asset. A complex, lengthy and overly aggressive set of terms in the LOI will likely force a drawn out process that could backfire. This does not mean that you should be sloppy when constructing your Letter of Intent, but know that many deal terms and closing conditions will become much more formalized as you move forward through due diligence and begin to structure the definitive deal documents (a.k.a The Contract).

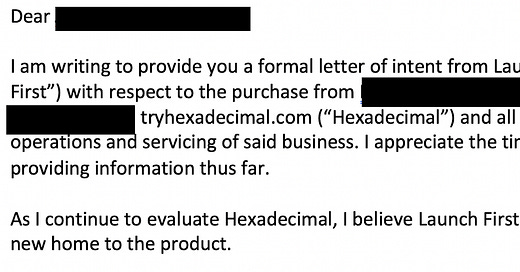

By the time you are crafting your Letter of Intent, you will likely have had at least a few discussions with the seller and a sense of basic business operations. Some sellers may request a formal NDA before sharing certain information. NDA’s are particularly common if you are acquiring a larger business or a business you already compete with. The founder of Hexadecimal was already incredibly transparent in public about the operations of his business, so much of this formality was unnecessary.

When navigating through this process, keep in mind that the legal framework is important but the end goal is to develop trust between buyer and seller. Trust will bring the deal across the finish line and prevent either party from getting cold feet.

Like your invitation to the homecoming dance, make it clear that the LOI is non-binding. I am not a lawyer, but it should be obvious that in the event you find a hornets nest (or several) during due diligence you will want a way to cleanly back out of the arrangement.

Layout the offer in as clear of terms as possible. Again, remember that the LOI is a framework from which to move forward. You can always clarify or change agreed upon deal structure in the final deal documents (earn-outs, cash vs stock, closing conditions etc.).

In layman's terms: I was gonna pay cash, only buy assets (not equity), give both parties 30 days to close from contract signing and, release the whole payment at once. This is about as simple as an acquisition can be. I tried my best to outline what I believed to be the core assets needed to operate the business (see below). Knowing this was going to change I made it clear in the LOI that these terms were not definitive and subject to change per the definitive deal documents I would draft (more on those later).

The definitive deal docs would go on to outline additional items such as subscription information (Stripe account) and customer goodwill. Customer goodwill is a fancy term for the accounting value placed on a customer's willingness to continue paying you for services (e.g. your brand’s value).

With deal terms outlined, I had to come up with a reasonable set of diligence requirements. In larger, more complex acquisitions the due diligence requests can span thousands of detailed document requests; from sales collateral, to software licenses, to payroll history, and employment agreements. Knowing this business was a one-person operation, I only needed a few dozen things to be confident I was not buying a pig with lipstick.

Due diligence requests made in the LOI are never exhaustive and typically are only outlined at a high level (e.g. financial statements, sales contracts etc.). I wanted to make it more explicit as to what I would need to start the process and I knew that I could always request additional information if questions arose.

In addition to noting the initial diligence items required, I framed the core closing conditions that had to be met to trigger release of payment. These included:

Sign a 12-month restrictive non-compete agreement

Sign a 3-month advisory agreement

Sign a consulting agreement that included 25 hours

Operational infrastructure completely transferred into Launch First possession

All marketing assets transferred into Launch First possession

All domains and IP transferred into Launch First possession

Looking back, there was one mistake I did make in my LOI that luckily did not bite me the ass; I forgot to include a no-shop clause. Think of this like an engagement ring (except with legal repercussions) that prevents the seller from dating during the no-shop period (typically ranges from 30-90 days). Because the deal was so quick to close (about 12 days from LOI to closing), this mistake thankfully didn’t cause any issues.

As one other parting piece of advice, one that I will make regarding all deal documents, please consult an attorney. If you don’t have legal counsel already in your rolodex of contacts, finding an attorney to review documents can be as simple as going to UpCounsel or Rocket Lawyer.

I sent this over to the seller via DocuSign and within 12 hours we had a signed LOI and could begin the due diligence process. Next week I will cover the due diligence process (spoiler alert: it went smoothly) and the definitive deal documents in detail.